Why You Should Always Proof in Print

After reaching the point I felt my novel was buttoned-up and fully set, from the cover to the copyright page to the ‘About the Author,’ and had run the options gauntlet toward self-publishing my novel through CreateSpace, I was given two proofing options: online (via my browser or a PDF), or with a print copy.

I picked print. And, for me, digital was never really an option at all.

Forget the fact I want to see how the cover looks before ordering copies (and I’m terribly glad I did with my most recent title, as the cover simply didn’t work at all) because the print proof, while carrying a minor cost compared to the free digital version, offers a slew of benefits you just can’t find on a screen.

I’m a sick man.

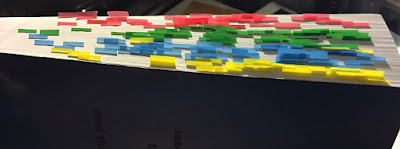

That’s all I can think of when I look down at the proof of my latest novel, The Nobodies, flagged as it is on practically every page. Though the content is, of course, identical both on- and off-screen, the majority of these notes highlight repeated words or phrases, which, for a reason that escapes me, stand out more readily in print than in digital.

In one case, for instance, I referred to a certain MacGuffin (a phrase which downplays its importance and development, but we’ll use it anyway) as “the device” four separate times across just three pages. Now, maybe that wouldn’t have bothered others. Maybe no one else would’ve ever even noticed it. But man, did it grate on me.

And not once did I pick up on it when looking at the book on-screen.

The same could be said for the handful of typos I found. All but one were missed punctuation marks likely accidentally dropped in the last round of edits, but that one—well, let’s just say it was such an amalgam of a misspelling that I couldn’t help but snort a laughing groan at the mistake.

There’s a bit of an illusion in play when finalizing with a print proof: instead of working on a book, you’re reading one.

This may seem inconsequential, but it’s an important distinction.

Imagine you’re reading a book by another author. There may come a point where you simply disagree with a decision or direction, or you might wish something was done a different way or a certain character/event given better development.

Part of you, when you’re reading your proof, will start to do this with what you have written.

Such a process occurs during the construction of your novel, of course; otherwise, edits would never occur or be of any significant measure. But the difference here is that you believe this to be the final copy, the final version of your story, the one you should only need to verify is free of typos.

So when that nagging voice in the back of your head starts to say to you, “Wouldn’t it be better if this character sacrificed themselves two chapters ago instead of here?” or “That character’s reaction didn’t feel natural. They didn’t earn that.” it’s important you don’t simply dismiss them, though you may think your work already done. There’s a chance one or more of your readers will think the same thing.

Perhaps of most import when proofing is taking a break from your work and coming back to it with a fresh perspective and renewed energy. I’m not talking a few days or even a week—a break of at least a month or two can help you see your story and its structure in an entirely new light.

But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do anything with that time. And I don’t just mean go work on another book.

If you’ve got your proof copy in hand, ask someone to read it for you. While the notes above apply to you, they’ll doubly apply to someone who hasn’t spent as much time with your story as you have. And in my experience, readers tend to give the most feedback to copies they can hold in their hands. I’m not sure if it’s just the concept of making their physical mark and feeling accomplished for it, or, like I said, something different triggered in the brain, but while a digital copy may result in notes like “I’m not sure about this character…” I may see something more akin to “How is this happening!?” in print.

You can see the difference in the energy there.

On a personal note, two of the greatest pieces of feedback I’ve ever received came as a result of readers checking out print copies. I’m not going to go into them now, and maybe I never will, but I will say I’m still learning from their profound repercussions years later. As a matter of fact, after reading through my most recent proof, those bits of age-old feedback helped me realize one character’s arc and conclusion is inherently flawed. Because while I know what’s in store for this character, readers don’t, and the place I leave them in isn’t nearly as satisfying as it should be.

That needs to change. It probably helps that I love the character. And have plenty, plenty more in store for them.

Something of which I’m actually working on now. Back to that.

I picked print. And, for me, digital was never really an option at all.

Forget the fact I want to see how the cover looks before ordering copies (and I’m terribly glad I did with my most recent title, as the cover simply didn’t work at all) because the print proof, while carrying a minor cost compared to the free digital version, offers a slew of benefits you just can’t find on a screen.

Repetitions and Typos Pop in Print

I’m a sick man.

That’s all I can think of when I look down at the proof of my latest novel, The Nobodies, flagged as it is on practically every page. Though the content is, of course, identical both on- and off-screen, the majority of these notes highlight repeated words or phrases, which, for a reason that escapes me, stand out more readily in print than in digital.

|

| Not even sure why I bothered with the tabs. |

In one case, for instance, I referred to a certain MacGuffin (a phrase which downplays its importance and development, but we’ll use it anyway) as “the device” four separate times across just three pages. Now, maybe that wouldn’t have bothered others. Maybe no one else would’ve ever even noticed it. But man, did it grate on me.

And not once did I pick up on it when looking at the book on-screen.

The same could be said for the handful of typos I found. All but one were missed punctuation marks likely accidentally dropped in the last round of edits, but that one—well, let’s just say it was such an amalgam of a misspelling that I couldn’t help but snort a laughing groan at the mistake.

It’s a Trick of the Mind

There’s a bit of an illusion in play when finalizing with a print proof: instead of working on a book, you’re reading one.

This may seem inconsequential, but it’s an important distinction.

Imagine you’re reading a book by another author. There may come a point where you simply disagree with a decision or direction, or you might wish something was done a different way or a certain character/event given better development.

Part of you, when you’re reading your proof, will start to do this with what you have written.

Such a process occurs during the construction of your novel, of course; otherwise, edits would never occur or be of any significant measure. But the difference here is that you believe this to be the final copy, the final version of your story, the one you should only need to verify is free of typos.

So when that nagging voice in the back of your head starts to say to you, “Wouldn’t it be better if this character sacrificed themselves two chapters ago instead of here?” or “That character’s reaction didn’t feel natural. They didn’t earn that.” it’s important you don’t simply dismiss them, though you may think your work already done. There’s a chance one or more of your readers will think the same thing.

Passing the Buck

Perhaps of most import when proofing is taking a break from your work and coming back to it with a fresh perspective and renewed energy. I’m not talking a few days or even a week—a break of at least a month or two can help you see your story and its structure in an entirely new light.

But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do anything with that time. And I don’t just mean go work on another book.

If you’ve got your proof copy in hand, ask someone to read it for you. While the notes above apply to you, they’ll doubly apply to someone who hasn’t spent as much time with your story as you have. And in my experience, readers tend to give the most feedback to copies they can hold in their hands. I’m not sure if it’s just the concept of making their physical mark and feeling accomplished for it, or, like I said, something different triggered in the brain, but while a digital copy may result in notes like “I’m not sure about this character…” I may see something more akin to “How is this happening!?” in print.

You can see the difference in the energy there.

On a personal note, two of the greatest pieces of feedback I’ve ever received came as a result of readers checking out print copies. I’m not going to go into them now, and maybe I never will, but I will say I’m still learning from their profound repercussions years later. As a matter of fact, after reading through my most recent proof, those bits of age-old feedback helped me realize one character’s arc and conclusion is inherently flawed. Because while I know what’s in store for this character, readers don’t, and the place I leave them in isn’t nearly as satisfying as it should be.

That needs to change. It probably helps that I love the character. And have plenty, plenty more in store for them.

Something of which I’m actually working on now. Back to that.

Comments

Post a Comment